The Dances

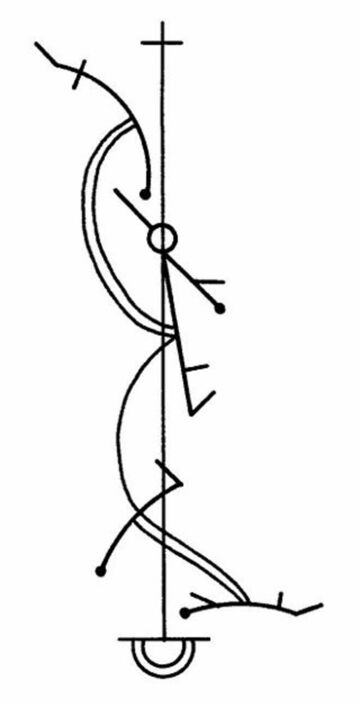

There are over 350 extant dances published in notation. There was a basic vocabulary of approximately twenty steps, though these were performed with many subtle variations and at least 20 different types of dances were notated, their names familiar from the dance suites of baroque composers. The minuet became a rite of passage at courts across Europe. Dances can be categorised in accordance with their basic rhythm:

duple rhythm: bourée, gavotte, rigaudon, etc.

triple rhythm: chaconne, courante, minuet, sarabande

compound duple rhythm: canarie, forlana, gigue, etc.

French contredanses (the French adaptation of English Country dances) were given in simpler notation. Fleurets or pas de bourrée were generally used, with full notation only for more unusual steps such as pas de rigaudon.